I understand that critiquing is easier than correcting, and if you're in the education space I don't mean any offense. I just wanted to make my views public and get them out there.

Without directing my drive and motivation towards creating things I go stir crazy. I see it every semester, I get bored of school after a week and start an overly ambitious project that pulls my time away from studying. Instead of Netflix or going out, you'll find me procrastinating by building things. You would think it's akin to a passion vector for anything engineering related, including school - but this is not the case. Waterloo might be specifically bad, maybe it's not even Waterloo, maybe it's my program or even my specific class's poor luck. But a string of bad teachers, and horrible organization (especially through COVID) has made me realize that I have been scammed. Scammed out of around 64k dollars, not including the cost of textbooks that are surely needed when the professors are as inadequate as they are.

Another problem I've noticed is that professors just don't care. A lot of them just want to work on their research or if tenured, do as little work as possible. These professors are required to teach a certain amount of courses (full-time faculty in the professorial ranks are expected to teach at least 2/3 semesters), and so a lot of the time they care very little about the quality of the education they provide. At least one of my professors every semester falls into this category. This seems to be one of the root causes of why students aren't motivated, because the professors aren't motivated either. This leads to low energy and poor quality lectures, labs that aren't challenging, and assessments that don't make you think. Not having challenging material and withholding valuable feedback leads to students that slack off and don't learn from mistakes, for instance take a look at my most recent Design and Dynamics of Machines quiz distribution.

Now like I said before, I have no proof if this is a University problem, a Waterloo problem, or my program/class, and I would love to hear about the conditions at other schools. Regardless of the answer to that question, I firmly believe that our approach to learning is broken. Currently, my program requires 5-8 hours of straight focusing in lectures with a 1 hour break, and I leave the lectures with nothing more than "wow I have a lot to catch up on" every day. Then in order to stay on top of content there's around 2-3 hours of homework and reading to be done. There are few profs that are actually interesting enough to pay attention to, and even then they tend to not understand how to describe, articulate, or focus on the actual challenging concepts. All too often the most amount of class time is spent on easy concepts, leaving no time for the complicated stuff until it appears on the exam. Speaking of exams, of all the 25+ courses I have taken, almost all of the ones students considered "fair" or "easy" were just regurgitation of the problem sets and practice exams. And the ones that actually make you think? The ones that check your deep knowledge of the material? They're considered too hard and get curved up. The professors get scared of bad ratings and negative feedback and change the way they assess in order to be more predictable. All but 2 courses I have taken in my post secondary career had the exact same theme of questions as the previous year. Now mind you, my grades are very happy about this, but I can feel it poisoning my brain, rewarding it for not learning or thinking but recognizing patterns instead.

I had a grade 12 advanced calculus teacher that was fantastic at avoiding this, everyone hated him but me. He would put an entirely new type of question on the tests, or even introduce new concepts to learn in the test. I understand it sounds horrible, I hated it too at the time. But after getting the satisfaction of solving a couple correctly and developing a deep understanding of the content, I came out thankful. He really demonstrated to me what real testing meant.

Another controversial example of this was my sensors and instrumentations professor. Everyone who did mechatronics at Waterloo knows who I am talking about, he's been teaching the course since before my parents met. I am talking about James Barby and MTE 220, a right of passage for Waterloo mechatronics engineers. I was the last class he taught, and I think towards the end of his career his effort started to taper off. But his questions really made you think, he was tough and unrelenting. Sadly given that he had taught the course so many times, all challenging questions had basically been repeated in previous years, and a lot of the assessments were still pattern recognition.

One of my closest friends has stopped going to class entirely, and then days before exams just learns the types of questions on previous exams. Like I stated before; it's simple pattern recognition, our brains are great at it. He consistently gets higher grades than me, yet puts in a percentage of the amount of effort. For the last two weeks of my current semester I did the same thing, and read the equivalent chapters in the textbook. It takes a lot of motivation to pick up a textbook and read it when you could be doing a bunch of other things instead of school. Despite this, I found that the textbook was more engaging than most lecturers, it gives great examples and more intuitive explanations. You could argue that if you really wanted to learn you would go to class and it wouldn't matter what was covered by the assessments, but then at that point why do assessments exist? Would people really go to class if there weren't assessments? Why wouldn't we see random unenrolled strangers attending lectures? Everyone's doing it for the degree, and that means passing the exams.

After school went online in 2020 it was revealed how disorganized the university truly was. Almost every class used a different video conferencing software, by the end of 2 semesters online I had:

- Microsoft Teams

- Zoom

- Bongo

- WebEx

- WebEx Training (yes apperantly thats a different version)

- Google Meets

- Some fake Zoom that I can no longer find

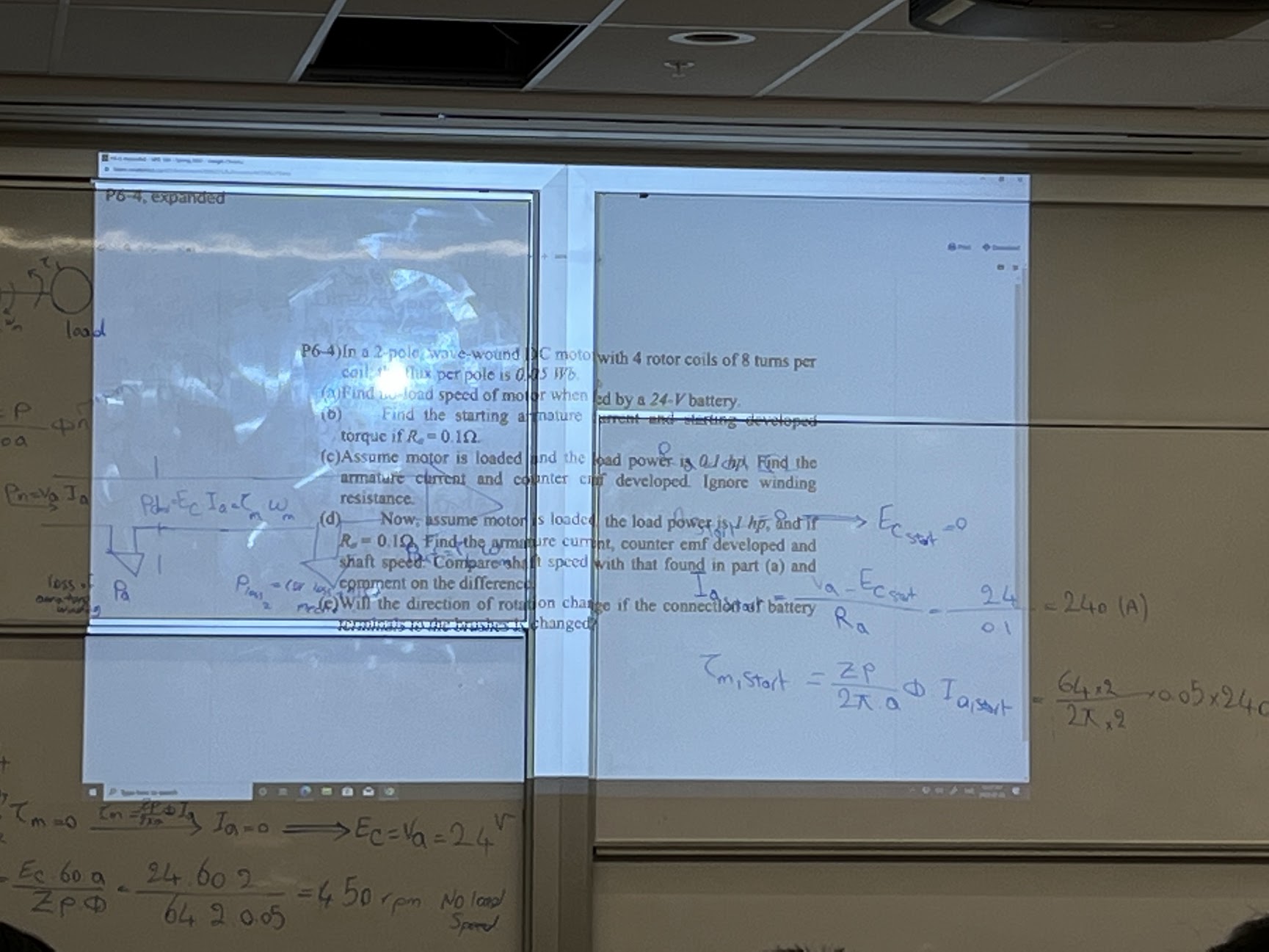

Out of the 17 classes I took online, only 1 of them knew how to properly mute the whole class and use the admin controls all these softwares offer. The rest were a wild west of interruptions, and pure incompetency when things went wrong. In 2021 when things went hybrid it got even worse, now instructors needed to take questions from in person and online, while simultaneously video streaming the whiteboard or screen sharing. Only a handful of professors stayed on top of this, the rest were such a disaster most of the class would stop showing up to weekly lectures (one specific class had <10 people a lecture for 3 months straight). One class had such a bad internet connection that attending online was completely impractical. Even now in 2022 that were back in class, instructors still aren't taught how to use the controls in the classroom for the projector, microphone, or overhead lighting. They can't even make consistently formatted assignments, or the assignments aren't even legible (see below).

Another thing I think is horribly broken is labs. I haven't had a good experience since my first semester. Most of the time there's no purpose or application given for what you're doing, so they feel pointless even though they're supposed to be the application part of our education. For all the labs I've had, there is a strict guide that tells you exactly what steps to do and how to do them so that you don't break equipment, but this just makes followers - and to quote Tom Peters, "Good leaders don't create followers, they create more leaders.". The labs should instead be designed to teach students how to fail, let them blow stuff up (but make sure it's on them when it does). This is how I learned practical skills as a kid, and it worked very well. Not having a lot of money and having a small collection of electronics parts meant I couldn't afford mistakes, I had skin in the game, so I had to trust myself and truly understand what I was doing. Current labs are the opposite, my actuators course has us plugging in wires into $10k machines that the university obviously doesn't want to break, so they tell us where every single wire goes and make us double check it. The one exception to this is MTE 220 (shoutout) where there were lots of custom designed parts, and plenty of opportunity to break things.

When asking peers what they've learned at university, a lot of them can't recall details. For example, when asking a friend about his circuits course he didn't remember how to wire an op-amp, or what the pinout was, or even what it did (he gave a subpar explanation). When asking him why he's in school if he isn't remembering content he said "I think school is mostly about learning to learn". Are you really learning how to learn? Or are you learning how to pass? Post secondary started as a way to train professionals for the workplace, but it has evolved into turning students into pattern recognizing machines - the worst way to learn. This will only get you so far in the real-world. In order to properly innovate you need to deeply understand first principles, not just doing things "because we've always done it that way" and repeating the pattern of our priors.

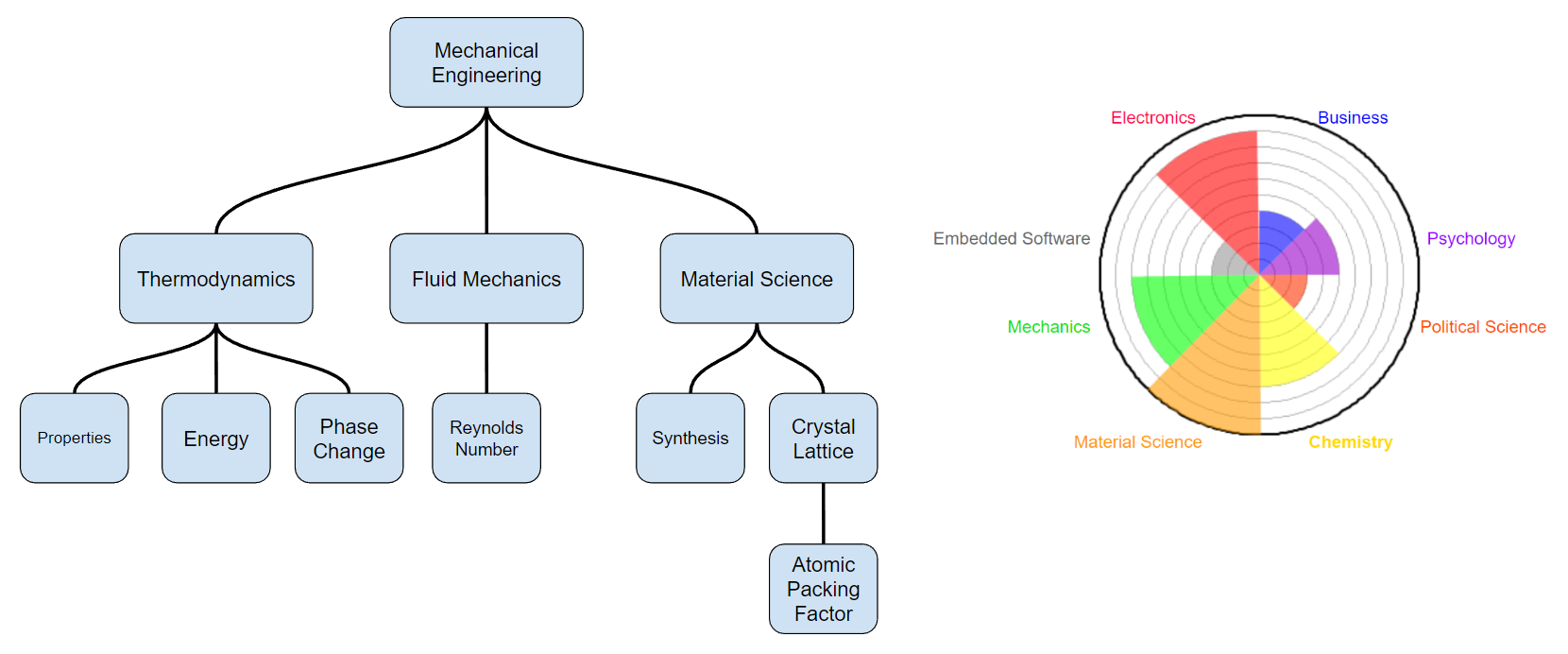

Another mediocre benefit of modern school is learning what exists in the first place, and knowing what to search for when you get stuck. This is very valid, but I don't think it's worthy of much credit. Informing people on what exists is much easier than teaching it to them. For example, explaining that Kalman filters are used for processing sensor data as opposed to explaining how they work and how to implement them. If this were the only benefit of modern education, a degree could be completed in a single semester. But like I said, this is still very useful. I often don't realize how little I know and end up in the Dunning-Kruger pit of despair but then again, it's fun to be enlightened. I think something as simple as a good visual of showing people what they know and what they don't know would be sufficient. A multi layer radar chart comes to mind, where a tree of knowledge broken down by levels (ex. Engineering -> Mechanical -> Materials -> Crystal Lattices -> Atomic Packing Factor) would be coloured in as you learn things in class and understand them. That way you can really see how little you know about Biology, but recognize that you have a pretty good grasp on modern materials. A basic MVP of this would literally just be turning Wikipedia into a hierarchical tree and having people check off what they know. A mock up of this idea is shown below.

So why do I enjoy working on projects so passionately, and why do I get obsessed with working on them? Because I can feel myself actually learning, and it's very fulfilling to complete a project. I'm also as stubborn as a mule and never give up. Mainly it's the process of:

1. Working towards a goal or idea

2. Running into a roadblock

3. Researching and learning to overcome a roadblock

4. Fixing the roadblock

5. Repeating until the goal is met

The main point here is that the motivation isn't learning, learning is a side effect. You might think you're motivated to learn, but that's likely not true - I mean you aren't reading textbooks because you enjoy it, right? The motivation is getting the project done. That's what you want to do. Learning happens when something blocks you from achieving your goal, and you figure it out, building critical thinking skills. In school, you are given solutions to roadblocks you don't even have so your brain doesn't think they are important. When labs and assessments come, they ask for solutions to road blocks that you may not associate with what was learned earlier. Most of the time, an assessment in school is not a roadblock, it's a goal, to pass the assessment. And with no thinking problems on modern assessments, there is no reason for students to critically think.

I see the same pattern at work that I see in my personal projects. I've found that I'm also motivated in the workplace, my passion lines up with my work and I am very lucky for that. It ends up being the same process. There's a team goal, you run into roadblocks, figure out how to fix them, learn a bit, and repeat. So why does school teach us to learn in the opposite way?

Let's move away from the traditional lecture style that's as old as history itself. Let's take some of the best experts in every subject and use the internet to extend their reach. They can provide the information that fills in the aforementioned patches, and unblock the roadblocks. Khan academy, Coursera, and even the Organic Chemistry Tutor (who does much more than organic chemistry) already do a great job of this. A lot of the students I know find out what they need to learn in class, then go online and find 3rd party content to actually understand it properly. My biggest gripe with these resources is that they function just like normal school. Hold that thought.

At the very least, schools should teach after they question. What I mean by this is instead of learning a skill and then afterwards demonstrating the skill in labs, have students get stuck on a problem (in a lab for instance) because they don't have a skill, they'll be motivated to learn it in class, then have them finish the problem.

Khan academy and other online resources are only used when students are stuck on homework, and need to overcome that. It's proof that struggle makes people want to learn.

The main concern that I hear when I pitch this is "won't students have gaps in their knowledge since they're only learning when they run into a problem?" The answer is yes, but it won't matter. First of all, projects should be designed such that the road blocks will cover as much taught in the course as possible, ie. make almost everything a problem. This will reduce the amount of gaps and I'm confident it could exceed the current knowledge retention of students at modern educational institutes. Second of all, if the projects are big enough and comparable to those found in industry, why does it matter? If they are capable of completing the project and learning how to learn, they are better off with holes in their knowledge than having some useless knowledge they'll forget as soon as exams are over.

I think it would be really powerful if each course (or multiple courses working together) required you to work on a passion project each term, and labs were time to work on your project. In the first semester of mechatronics there is something similar to this, there is a project that bridges intro to design and Digital Computation. Each group is given a Lego mindstorms kit and they have to use a certain amount of sensors, motors, and software elements taught in class. It worked really well, I think the entire class learned more in that project than in both courses combined. Why? Because the knowledge and lessons stuck to them, their brains realized that what they learned was important. Every semester has at least 3 courses that overlap and could have a mutual project; this number could be higher if the semesters were rearranged.

If university courses had projects that resembled those found in industry, with tough challenges to overcome, students would be motivated to use the offered content to learn the material. And they would be better prepared to learn on their own to overcome tough challenges, which is what real world engineering is all about.

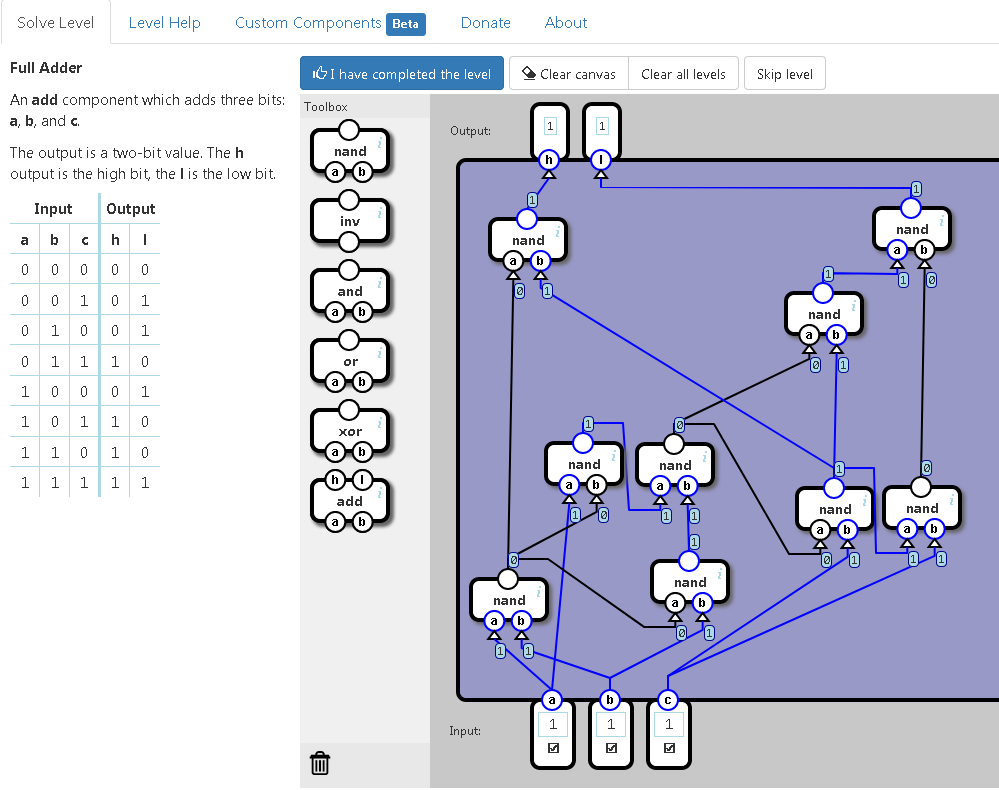

There's a big disconnect in between courses regarding knowledge transfer, causing a lot of unnecessary relearning. I propose a note taking app of sorts, where students slowly build a calculator of sorts for all of their courses. Take the beautiful website NandGame.com where you slowly assemble a digital logic circuit from basic building blocks. You start with relays then build gates, then arithmetic, and eventually a processor. At each stage your circuit is tested to ensure it has the correct logic. This ensures early errors don't propagate forward throughout the project. I think something similar could encompass a lot of physics courses and could connect the dots between a lot of different courses. Think NandGame combined with LeetCode but for school. Your answer would be checked thoroughly, and it could make sure you aren't guessing and checking. Instead of solving kinematics equations by hand, you would write code of sorts to calculate the same thing and your code would be verified with many different scenarios. Then, when a future course has a kinematic element to it, you already have the supporting calculations. This would force a consistent variable naming scheme, calculation, and progress status of course progression. It would also allow courses to share content and flow into each other easier. A good example is right now in my systems modeling course (SYDE 351) we have learned how to model and solve circuits (MTE 120 and MTE220), motors (MTE 320), spring mass damper systems (MTE 202), and even thermal systems (MTE 309). In all of these cases the same or similar equations were used, and retaught. If the professor used the same conventions and equations, this course would be reduced to almost nothing since we would know all of it already. Another analog to this proposed system is how python has libraries for everything, and you rarely need to write functions from scratch. The libraries contain functions that only have to be written and understood once, and then they can be abstracted. This is a powerful practice in engineering, and heavily reduces the complexity of problems.

Modern day engineering programs are so jam packed with content, it might even be required that you don't deeply learn everything. Maybe I'm thinking of this backwards, maybe I'm not supposed to be fully learning everything. The sheer amount of content covered every semester is a lot to digest, and the students in my class that I associate with learning deeply are almost always studying. If I had to guess, I would say that by making learning more efficient, it wouldn't take as long to deeply understand everything. But even if it did, what's more useful in the real world? A light remembrance of a ton of topics, or a deep understanding of core material?